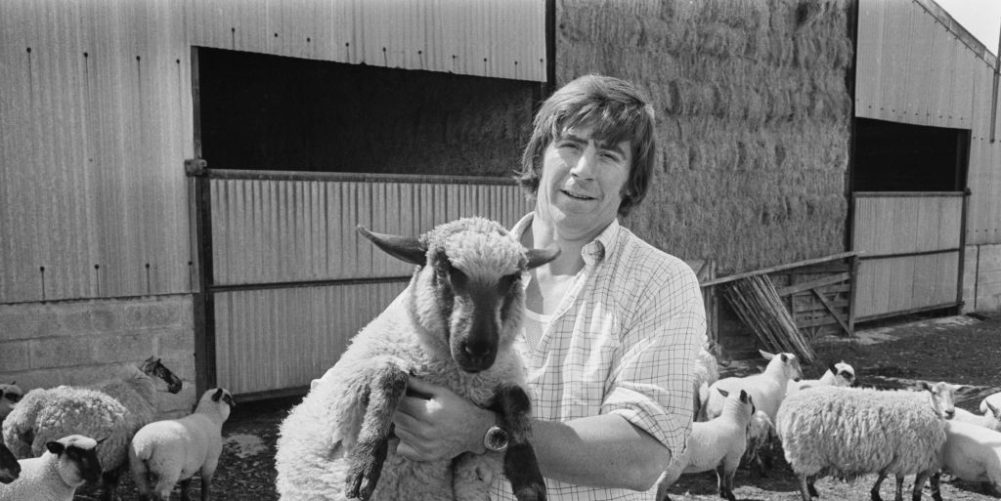

Peter Jackson pays tribute to the former England captain who has died at 79

During the retreat eastwards from their team's thrashing at Cardiff Arms Park, two England selectors stopped at John Pullin's farm beneath the Severn Bridge.

They had called not to carpet the captain for conceding five Welsh tries without reply during the mismatch the previous day but to ensure he would not be ducking out of the next one, Ireland in Dublin.

The summit at Pear Tree Farm on Sunday, January 27, 1973 would change the course of Anglo-Irish history.

Scotland and Wales had opted out of the Celtic Brotherhood the previous season by refusing to honour their fixtures in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday. England had infinitely more reason to be fearful of venturing into the midst of a war.

The selectors, ex-Bath flanker Alec Lewis and former Northampton prop Sandy Sanders, had been deputed to inform Pullin that England would be sending a team to Dublin as scheduled come what may, even if it meant cobbling one together from a bunch of old boys' clubs.

Pullin needed no persuading. “We had lunch and a chat,'' he told me. “I decided I'd go to Dublin and they said: ‘Do you think the others will come?' I said: ‘I don't know. It's up to them.'

“At the back of your mind you thought: ‘Well, I know if I don't go, they will find a hooker to play for England eventually, even if he would be the 25th choice. They preferred I went as captain and I saw no reason why I shouldn't.

“I didn't feel in any danger as a sportsman. I knew the Troubles were fairly widespread. I wanted to play. Deep down, I never thought we would be a target as a sporting team. For that reason, I think Wales and Scotland should have gone.''

England did manage a try, from Tony Neary, but without ever threatening a rude response to the longest standing pre-match ovation in rugby history. Pullin's postscript in front of 200 guests at the black-tie dinner in the Shelbourne Hotel – ‘We may not be much good, but at least we turn up' – set him apart from other England captains.

He could never quite understand why it became a source of recurring acclamation, ironically so given that its author was never one to waste two words where one would suffice. “I didn't think it was that good a quote,'' he said some 40 years later. “It just seemed the obvious thing to say, didn't it?''

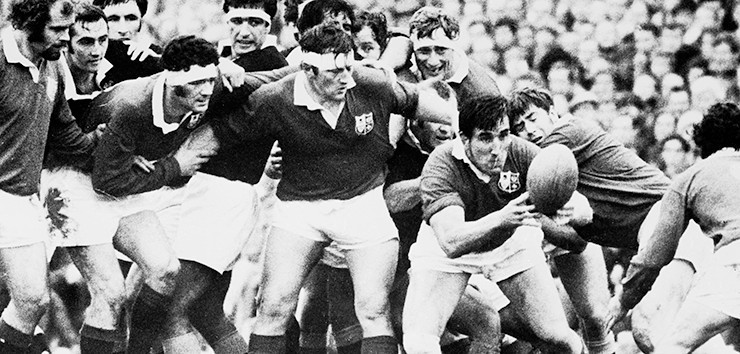

Pullin deserves to be remembered first and foremost as a hooker great enough in the mid- Seventies to be voted by a panel of global experts as the best in the world. His place in the Pantheon had long been assured by a series of mighty achievements, not least being the solitary Englishman to play in all four Tests when the Lions won the 1971 series in New Zealand for the first and only time.

Two years later, his was the only non-English pair of hands in Gareth Edwards' try of the century for the Barbarians against the All Blacks.

He was the first captain to lead England to victories over the All Blacks, Springboks and Wallabies, a feat which would remain unequalled until Martin Johnson matched it some three decades later. Even then, Pullin's still reigned supreme and not because all three victories came within a period of 18 months but because they were achieved against the odds.

The first, at Ellis Park, Johannesburg on June 3, 1972, proved to be his finest hour. The bald facts of England's 18-9 win, based on five Sam Doble goals and Alan Morley scoring the game's only try, says nothing of what really happened.

In a pre-substitute age when uncontested scrums were unheard of, a huge gash on Stack Stevens' forehead left the tourists with a hole on one side of their scrum vacated by the bleeding Cornishman. The other prop, Mike Burton, tells what happened next.

“We're doing well, holding our own in a very hard physical battle and then we lose Stack,'' he said yesterday. “The cut was so deep that you could see the bone in his head. It was horrible.

“Pullin looked at me and nodded so I switched from tighthead to the other side. John Watkins, making his debut in the back row, volunteered to step forward on the tighthead. That meant I was playing loosehead with no flanker behind me.

“So there we were: six thousand miles from home, six thousand metres above sea-level with a seven-man pack, half an hour to go and one hundred thousand at Ellis Park baying for more blood. We were up against a ruthless Springbok pack who treated us like dog manure on their shoes and, on top of all that, we had to cope with a South African referee.

“At the first scrum, Pullin looked at me again and nodded. He didn't say a word but we both knew what he meant. Something had to be done because we were up against monsters. Let's say we dealt with it in the way Gloucester props knew how.

“In all the mayhem which ensued, Pullin made sure we never lost a single scrum and there'd be about 30 a match in those days. That gives some idea of the bloke he was. A great player and a great captain.''

John Pullin, born November 1, 1941, died last Thursday aged 79. He is survived by his wife, Brenda, son Jonathan and daughter Mandy.

England Rugby legend, John Pullin, has died at the age of 79.

One of the most able hookers of his day, he was awarded 42 England caps between 1966 and 1976, the most for a hooker at that time, and seven for @lionsofficial

Rest in Peace John 🌹

— England Rugby (@EnglandRugby) February 5, 2021