PAUL REES TALKS TO PLAYERS AND COACHES ABOUT THE PRESSURES OF THE MODERN GAME

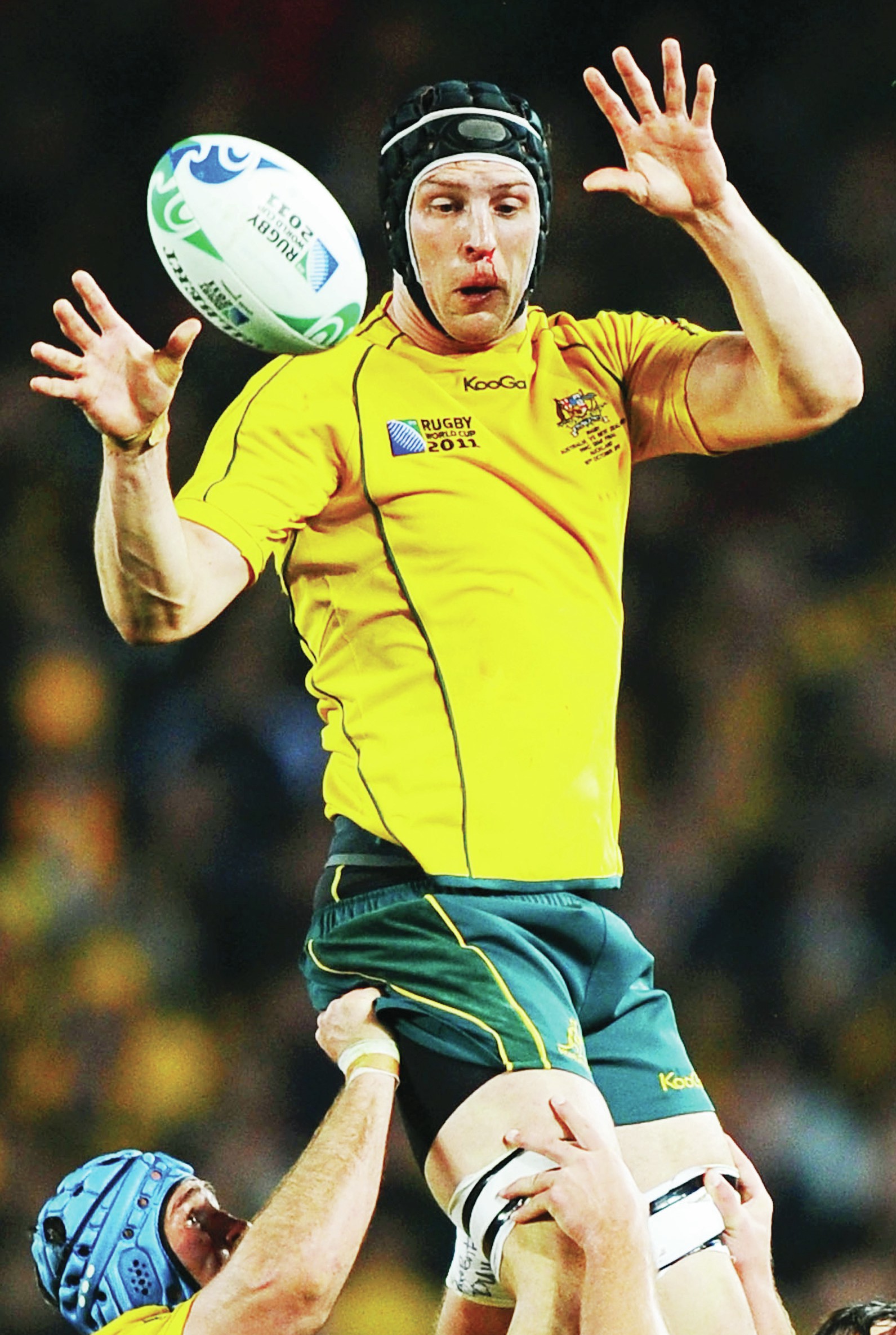

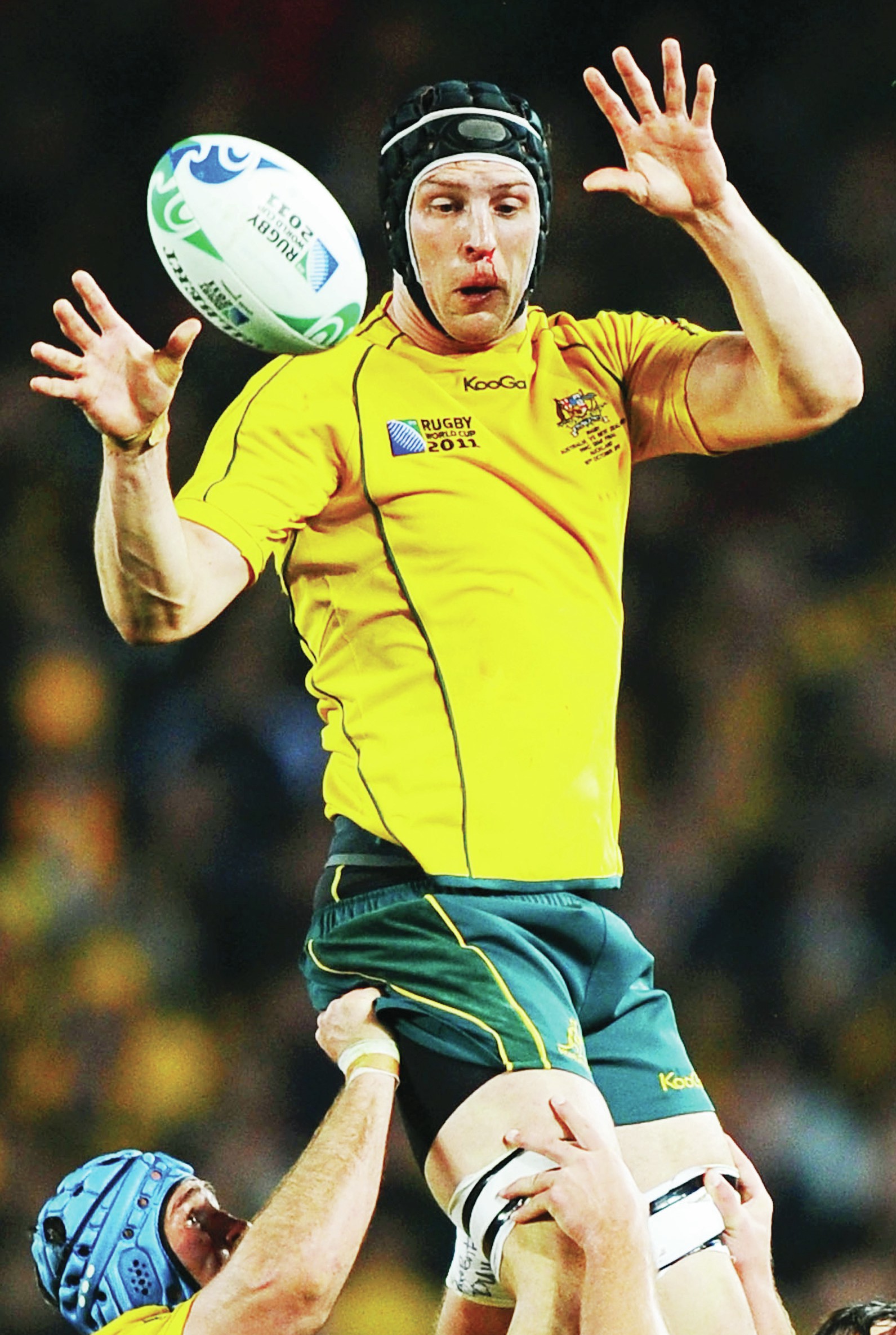

Dan Vickerman was the keynote speaker at a forum in Sydney about the issues elite athletes face once they retire. It was five years since a knee injury had forced the 63-cap Australia second row to retire from the game and he had told friends how difficult he had found it to adjust to life after professional rugby.

Vickerman never made it to the forum. He took his own life at his home in Sydney where he lived with his wife and two young sons. He was 37. “All of us at different times have had really dark periods post-football,” said his former Wallaby teammate, Brendan Cannon. “And Dan was one of those.”

Before Northampton’s match against Harlequins at Franklin’s Gardens on Friday night, the Saints’ former England hooker Steve Thompson was signing copies of his book that was published that day, Unforgettable: Rugby, dementia and the fight of my life. The 43-year-old said in an interview last month how he was put on suicide watch after being diagnosed with early onset dementia and suspected chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

“I sometimes find myself thinking the least selfish thing to do is just to kill myself,” he said. “That’s what this can do to me.” He is one of a number of players bringing a legal action against World Rugby, the Rugby Football Union and the Welsh Rugby Union. “I just want things to change. Rugby needs to understand the problem and stop lying about it.”

This weekend’s round of Premiership matches is being used to raise awareness of Restart, the official charity of the Rugby Players’ Association which relies entirely on donations. A player from each club is an ambassador for the charity and all the money raised will provide support for present and former professional players who are suffering mental issues through serious injury, illness or hardship as well as those who are struggling to adjust after ending their careers.

“The support offered by Restart has stopped a number of people doing a lot of silly things,” said the former England and Lions flanker, James Haskell, who is one of its trustees. “Mental health needs to be taken seriously and I am not sure enough players and coaches do. Restart has an anonymous hotline number and some 50 or 60 brave, forward-thinking players are using it. It has saved the lives of players.”

Ollie Hassell-Collins is the Restart ambassador at London Irish. “It is something that is really important for players,” said the wing, who was called into the England squad during this year’s Six Nations. “Players do take it seriously, but everyone can be made a bit more aware. It is easy looking from the outside to think that we are sportsmen who can handle it, but keyboard warriors need to understand what we go through.

“Since I have been at the club, a couple of players had to end their careers early and while we all have families to offer support, it is reassuring to know that a charity can help us. It is my second season as an ambassador for Restart and part of my role is stressing to players how important it is. It is all about spreading the word.”

Hassell-Collins is 23 with the bulk of his career to look forward to. Leicester’s ambassador, Freddie Burns, is 32 with one year remaining on his contract. The England outside-half has no idea what life after rugby will look like, acknowledging it will be a step into the unknown.

“I still feel that I have years in me, but realistically I know that is not the case,” said Burns. “You need to find a passion away from rugby and I have not managed that yet. I am not very academic and a 9-5 job would probably see me summoned by Human Resources after a couple of days.

“What scares me is the loss of identity you will suffer when you stop being a rugby player. In one way I have gone through it as a former England player. I won my last cap in 2014 and when you were in the squad you just made a call when you wanted a new pair of boots or even headphones. Everything was on the line.

“Then I was dropped by adidas and had to pay for my boots. It was an incremental tumble down the hill for me, but for those players who have long international careers, it is one hell of a cliff to fall off. I have felt that rejection and loss of identity and I have been lucky in that sense because it opened my eyes. I like to think I am mentally strong and resilient, but I know that life after rugby will be challenging, a step into the unknown.”

Burns is using his Restart role to advise young players starting out on their careers to plan for the future, saying that you can never do it too early. “I have made a few investments, but if I had done so when I was 20 I would be a lot better off,” he said. “That is what I am telling the young lads here: they are not going to be a rugby player for ever.

“Restart is hugely important. Ed Jackson is a mate of mine and the charity was a massive help when he suffered an horrendous accident. I have not used it much, but what matters is that it is there.

That is a huge comfort and this is a time when with the salary cap going down, players are having their wages cut or not having contracts renewed.

“At the same time, despite what we are told about player welfare being of overriding importance, some players are playing three games a week because squads are bare. They are putting their bodies on the line for less so how can they say they are looking after us?”

The RPA recently launched the Retired Player Network, a programme designed to support the health and well-being of retired members. The first step was the setting up of a network in which more than 20 gyms across England have signed up to provide bespoke offers to former RPA members. Many of the gyms are owned by former players, such as Phil Greening, James Forester, George Lowe and Jo and Alice Richardson-Watmore.

“When you play rugby, everything is planned out and is easily available for you,” said Lowe, the former Harlequins centre who was forced to retire at the age of 27 because of injury and now owns Milo and the Bull in London.

“When you come out of that environment it is not. By doing this, I can help players who have recently retired. It is free and gives them the opportunity to come into a new environment and build social connections, keeping them physically and mentally fit.”

The Gym Network will be followed by initiatives in areas such as nutrition, therapy and rehabilitation and secondary and tertiary care. “There has been talk for long time about the game as a whole looking at ways to do more for retired players,” said Mark Lambert, the former Harlequins prop who is the RPA’s head of rugby policy.

“We want the RPA to become the first port of call for retired players for wellbeing support post-career.

We have started that by creating the Gym Network and having spoken to and conducted surveys with retired players, removing that first barrier to get back into fitness and health, having something to work towards and having the ability to connect again, is key.”

Dan Carter is one of the most successful players in the professional era, starting his senior career seven years after the gates of amateurism had been stormed. After his retirement at the age of 37, he said that if he could change one thing in his career it would be to pay more attention to mental health far earlier than he did.

Rugby was seen as a macho world then and no-one wanted to show signs of weakness. “I think it was easier for us because we had work to distract us,” said Newcastle’s director of rugby Dean Richards, who in his playing days with Leicester, England and the Lions was a hard man among hard men.

“There were times when I would be working as a policeman the night after an afternoon match but now players think about rugby every day of the week and that makes the mental side important,” he said.

It is a time of the year which is stressful for head coaches and directors of rugby who have to tell players their contracts are not going to be renewed and inform academy players that they are going to be cut loose, shattering dreams.

“You do it with a heavy heart every time,” said Richards. “You do not sign a player with a view to releasing them and it is without doubt one of the most difficult parts of the job. It weighs heavily on you.”

Bristol’s director of rugby Pat Lam wishes Restart had been around when he was let go by Newcastle in 1998 after they had won the Premiership. “I was happy at the club and my boy was loving school there when I was suddenly sold to Northampton,” he said. “I had given everything for the club and was angry, feeling in turmoil, but it turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

“I met Ian McGeechan at Northampton and everything changed, leading me into coaching. What it showed me is that resilience is the biggest thing. Everybody goes through tough times: it is not a question of if but when. What you go through in a season as a coach and a player reflects life, highs and lows.

“You gain understanding through experience and you have to be aware when you go through a bad time. Reach out and have a chat. The stigma that you are somehow not tough enough if you do so has long gone. The awareness of mental health now is huge and rightly so. As a director of rugby you have to know your players and the people working with you and the values of rugby mean you look out for others.

“I went through dark times when I was a player, told to harden up or be considered useless, but there are different ways of doing it now. I was sacked as a coach by the Blues and was out of work for six months, but then I worked with Samoa and we got to seventh in the world. Connacht followed and for a coach what is important is not just to take a job but be clear what the vision there is. When you are not aligned with the owners, they will sack you.”

Newcastle’s Restart ambassador is Adam Radwan, the 24-year-old wing who was capped by England last year but has since got no further than squad sessions. “You have to keep working hard in competitive sport,” he said. “You have low moments but you have to keep working with a goal in mind believing it will come.

“I am self-aware and I have not been playing my best rugby this season. You have to be on top of your game to play for England and I have not been recently. It is a sport that demands a lot from you physically and mentally and you have to be able to switch off, which I do in fly fishing.

“Restart is extremely important for players. I have only been a professional for a few years but know guys who have had to retire early through injury. They give so much to the sport and it is good that there is support for them when their career ends. Mental health is important, as is preparing for life after rugby.”

An added pressure for players today is social media. Last year, some of the England football squad suffered racial abuse after the penalty shoot-out defeat to Italy in the Euro 2020 final at Wembley and rugby was among the sports that took part in a campaign to persuade the companies concerned to take steps to filter out such comments.

“Some players are incredibly good at batting social media abuse away,” said Northampton’s Restart ambassador George Furbank, the England full-back. “It is a pressure players in the past did not have and most players are on it in some form or another.

“It is great in some respects but it can be challenging. If someone goes through a bad run of form, they get blasted. It is not nice to see that and you cannot control someone slagging you off. I try to stay off social media when I am in camp with England. Rugby is incredibly challenging physically and mentally which is why having Restart is massive.

“People did not recognise mental health issues in the past but now they do. Restart provides practical support to players if they are struggling and it is fully confidential.”

Vickerman took a break from his career in Australia in 2008 to study land economy at Cambridge University. He captained the Light Blues for two years and played in two Varsity matches. He had a stint with Northampton before returning Down Under and featuring in his third World Cup. He worked for the Rugby Players’ Association in Australia but confided to former colleagues that he was having difficulties adjusting.

“We played together in an old boys’ team called the Silver Foxes and he expressed a number of times how difficult his transition was,” said the former Australia flanker, Owen Finegan. “It is for a number of professional sports people, particularly when you have had 10 years at the top. Everyone was shocked by Dan’s death. It was devastating.”

Rory Best retired after the 2019 World Cup having played 124 Tests for Ireland. “Restart is something important for players at the other end of their careers,” he said. “It always worries you that you are one injury away from retiring or one contract decision away. You never know what is coming afterwards and the stark reality is that the vast majority will not do well enough over the years to give themselves a cushion to retire and will have to go into something. You are a bit on your own and it is important to have organisations that can help you adjust when the bright lights dim.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login