LUCKY is not the word you would expect a player, who at the prime of his career broke his neck after diving into a swimming pool and became a quadriplegic, to call his autobiography.

But Ed Jackson, the former Dragons No.8 who numbers the England and Lions centre Elliot Daly among his close rugby friends, has since that day at a friend's house when he was told he would never walk again, looked forward, not back.

He has climbed mountains, literally and figuratively, and has used his experience to help others whose lives took an unexpected turn. He has set up a charity and led a trip to Iceland last month, taking two beneficiaries on an adventure as a form of mental therapy.

It was because he thought of others that Jackson very quickly after his accident kicked any temptation to feel sorry for himself not just into touch but out of the ground. It was his desire not to be a burden on his family, and his fiancée, Lois, for the rest of his life that drove him to defy medical opinion and, if not recover the life he had, be able to live what he had to the full.

“I have become used to a lack of function and underlying problems that affect my day-to-day life, but the pain I feel is all from rugby injuries,” said Jackson, who had seven operations during his playing days. “You ask whether it was all worth it and you cannot say yes or no because you do not know what it would have been like otherwise. But the values rugby gave me in terms of community have been invaluable and I have gained from it and felt the full force since my accident; it's invaluable to my current situation. You put you body on the line for your teammates and that is why you form such tight bonds.”

It was on a warm April day in 2017 when Jackson, then 28, accepted an invitation from family friends to have lunch and a swim in their pool. He was living in Cardiff having signed a two-year contract extension with the Dragons and was planning his wedding to Lois in Tuscany the following year. He had everything to look forward to.

As he prepared to dive into the pool, the ripples on the water made it look deeper than it was. He hit his head on the tiles at the bottom of the pool and when he regathered his senses, he could move only his head, not his arms and legs. As he lay helpless, he felt strong hands pulling him up and when he broke free of the water, he saw the face of his father, a retired GP, who made sure his son's head remained still as he lay in the water.

Jackson was taken to a hospital in Bath, a journey which took two hours rather than 15 minutes because his heart stopped beating three times. The driver had to pull over so he could be resuscitated each time by the doctor on board. An MRI scan showed he had dislocated two vertebrae at the bottom of his neck: the disc between them had exploded and nearly severed his spinal cord. He was transferred to a specialist hospital in Bristol and was told by the neurosurgeon that he may not wake up after the anaesthetic.

He came round the next day, unable to move and with only a tiled ceiling to look at. Although he had slight movement in his right arm, he was told it was unlikely he would ever walk again and what he should strive for was regaining the use of his arms so he could control a wheel-chair. Jackson aimed higher and started writing a live blog.

“When I looked back at it for the book, I noticed I used the word lucky 40 times in the first 100 posts,” he said. “I thought it was weird and then realised it was a coping mechanism to be able to deal with and rationalise everything. I was looking at the positives and I had been lucky in a number of ways.

“I was not dead and the first bit of luck I had was a thick neck, a legacy of being a professional rugby player, which stopped my spinal cord from being severed.

The second was that my father was a GP and knew what to do and I was just around the corner from a leading neurological hospital. The spinal surgeon, one of the best around, had just come back from holiday and was on call on a Saturday night. Given the severity of the injury, I have been incredibly lucky. I live with a lot of complications and life is not easy, but I am independent, happy and live a life full of purpose. It is a position I would have bitten someone's hands off to be in during the first few months of my recovery.”

Jackson's competitiveness as a professional athlete was a factor in his recovery, along with his willpower. “I do not know where that comes from, but a lot of it comes down to what you have to get better for. I was engaged and had a life that I enjoyed which I wanted to get back to. I noticed there were others in hospital who had no support network and did not have the same motivation. That is something I address in my charity, providing people recovering from a trauma, whether physical or mental, with a support network.”

The charity is the M2M Foundation. It's title, millimetres to mountains, reflects Jackson's progress from his first tiny steps to climbing some of the world's biggest peaks. “The idea for the charity came to me when I was climbing mountains raising money for charities such as Restart, the one run by the Rugby Players' Association which did so much for me,” he said.

“My motivation for taking on mountains is threefold: to challenge myself and push my body at a time when my previous goals, the next match or the next season, no longer existed; to motivate other people in hospital and show them that a negative prognosis does not have to be the case; and to raise money for charity. I had an epiphany when I was in Nepal: why not set up a charity and bring the people we are aiming to help with us?

“I died in an ambulance three times and what is life for if not to follow your passions? Lois and I set it up two years ago with the help of Olly Barkley (the former England outside-half) and we have raised more than £150,000 and taken beneficiaries away. It is the main passion of mine, but we take no money from it and that means finding ways of keeping a roof over our heads.”

Jackson delivers motivational talks to leading companies and is a presenter on Channel 4. He has covered rugby and will be part of the team in Tokyo for the Paralympics. “Working in television has been fascinating,” he said.

“You are part of sport, but from a different angle, the dark side as you call it as a player. The pressures of live television, the adrenalin, the chance you could mess up and being part of a team have gone a long way to replacing the buzz I had as a player.

“I have worked a fair bit with Sam Warburton. We came through age-group rugby at the same time: he captained Wales and I led England, although it is fair to say he had a slightly more impressive senior career than me. It only seems like yesterday that I was 18 and in an academy.”

When Jackson looks back on a playing career that started in Bath's academy and took in Doncaster, London Welsh, Wasps and the Dragons, he reflects on the physical toll it took: four of his seven operations were shoulder reconstructions and when asked whether he would encourage his children to take up the sport, he takes a moment before answering.

“There are inherent dangers in a contact sport. Players are becoming more and more powerful but while you can train to get your muscles stronger, you cannot get your brain to become tighter in your skull or your joints to become harder. Things have been put in place in the last ten years to the point where I am comfortable with where the game is at in terms of the precautions it is taking to a certain degree, but would I encourage my kids to play it?

“Absolutely, but I'm not sure I would do so beyond school or university unless they were a half-back. My body is wrecked: a lot of it has to do with my spinal cord, but when you are playing, loving what you do, you do not think about consequences.

“When you are injured, all you think about is playing again, but is it all worth it at the end when you are in pain every day? I cannot answer that because I do not know what it would have been like otherwise.

“I played on with injuries all the time and thought nothing of it and clubs need to get young players taking responsibility for their bodies: don't play when you are not fit because there will be long term damage and you will not be able to kick a football with your kids when you are 40. Rugby gets more physical every season and sometimes I cannot believe I did it.”

When he returns from the Paralympics, Jackson will attempt to become the first quadriplegic to climb Mont Blanc, accompanied by Leo Houlding, an ambassador for Berghaus, the outdoor clothing company.

“Berghaus have helped with adapting kit for the outdoors and I hope that has a knock-on effect with other people,” said Jackson. “I want to send a message that anyone can get off their sofa and reap the rewards of taking up a challenge. The charity has five big trips planned for next year if Covid allows. I used to be terrified by not knowing what was around the corner, but now I am excited by it, waiting to see where the world takes me.”

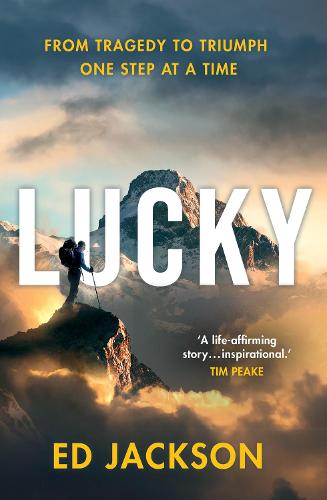

Lucky by Ed Jackson (HQ, HarperCollins, £20) is published on Thursday