Rugby Matters: Almond got it wrong but he was still right

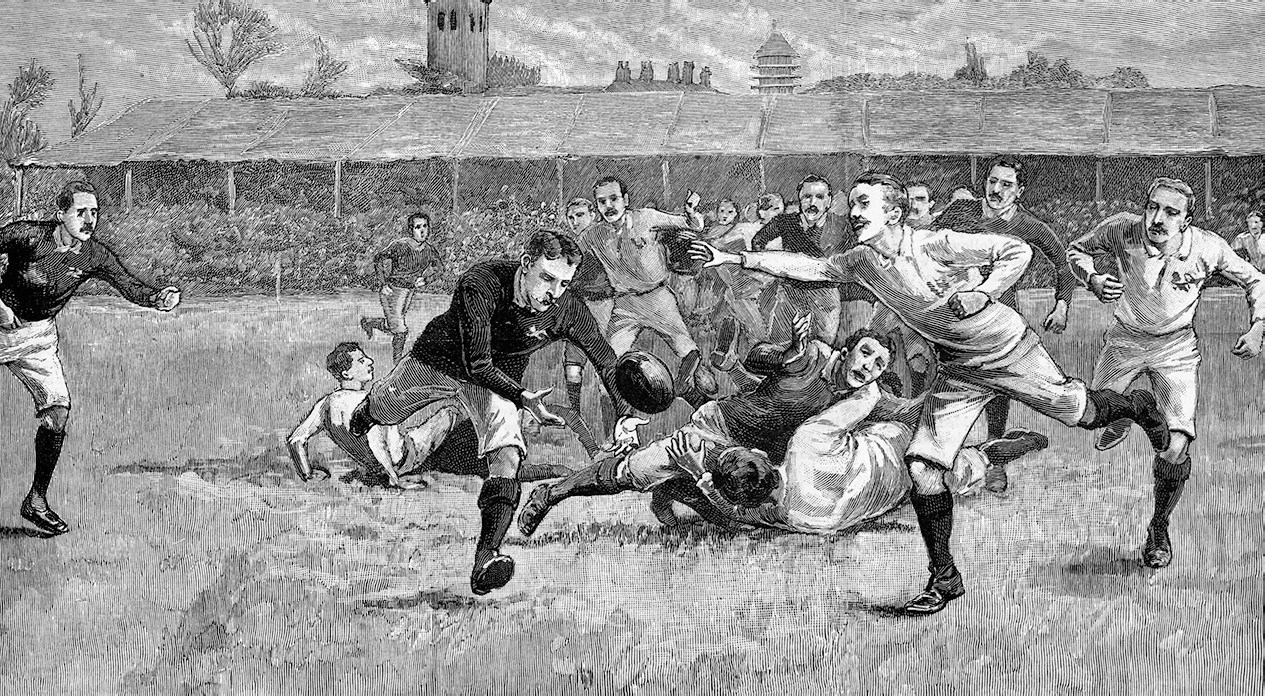

Saturday is the 150th anniversary of the Scotland v England fixture – the world's oldest international rugby match – and among many things a glorious chance to doff a cap to one HH Almond and his words of wisdom amidst the controversy and rancour that often attaches itself to this annual tribal gathering.

Hely Hutchinson Almond was the umpire that day, in effect the referee, in a sport that hitherto had optimistically asked the two captains to come to a mutual decision on key incidents and disputes. As if.

A redoubtable Scotsman and educationalist, Almond had bought Loretto School in 1862 and among other things turned it into a great centre of rugby. In total he served as headmaster, as well as rugby coach, for 39 years and was well used to dealing with stroppy, argumentative, testosterone-fuelled young blighters who were prone to “try it on” and bait authority figures.

And so it came to pass that in this first ever game between the old enemies that Scotland scored two tries, both hotly disputed by England.

The first, from a scrum, came from Angus Buchanan when England were still arguing that they had touched the ball down in goal moments earlier when Scotland's George Ritchie had lost the ball over the line. Instead a Scotland scrum was ordered by Almond.

This was a big call because the touchline conversion from William Cross proved to be the match winner – tries only being means by which you earned a kick at goal in those days. Scotland won the game one goal to nil.

Then much later came the ‘knock-on' controversy. In those days a knock-on was punished instantly south of the border if the ball went forward while up in Scotland they had the quaint but well-established notion that if the knock-on was not adjudged deliberate you could play on. Bless.

At a lineout on the England line late into the game, the ball was thrown in but Scotland's John Arthur clearly knocked the ball on before Cross fell on it over the line and claimed the try. Mr Almond concurred although this time Cross couldn't convert and the try counted for nothing.

England nonetheless went ballistic again shouting their protests, the air was blue, but it made no difference. Soon after Almond was invited to comment on the game and addressed the controversy over Scotland's first try:

“Let me make a confession: I do not know whether the decision which gave Scotland the try from which the winning goal was kicked was correct in fact. I must say, however, that when an umpire is in doubt, I think he is justified in deciding against the side which makes the most noise. They are probably in the wrong.”

In one fell swoop he had established two sporting maxims that have stood the test of time. First the referee is always right even when he is almost certainly wrong. His word is final. Suck it up.

And secondly the team making the most noise and kicking up the biggest racket about some incident or perceived misjustice are almost certainly in the wrong. Beware of those who doth protest too much.

Mr Almond would surely make hay these days with the constant chirp and chatter, strident demands for cards and ‘Hollywood's' that are creeping into the game. Matches under his control would, I suspect, end up as eleven-a-side affairs.

There was a move a few years ago for Almond to be elevated to the World Rugby Hall of Fame. He made the short-list one year, but he suddenly fell out of contention. I wonder if one particular country objected?

That match 150 years ago included a number of interesting characters as you might suspect. Right at the dawn of rugby time a reasonable claim can be made for Scotland's Alfred Clunies- Ross being the first international rugby player of colour being born on the Cocos Islands in the Indian ocean where his father, the island's colonial ruler, John Clunies-Ross, had moved with his wife S'pia Dupong from Surakarta. Young Alfred was later sent to Madras college in St Andrew's where he learnt his rugby.

Meanwhile, playing for England was a proud Scot, Benjamin Burns, a banker who had moved to London after studying at Edinburgh Academy. While working down south he became involved with the Blackheath club where he served as secretary and it was in a letter to Burns that the five senior clubs in Scotland issued their challenge to the clubs of England to meet in a 20-a-side international challenge game in Edinburgh.

Burns accepted the challenge on behalf of the English clubs and travelled north with the England party intending only to watch the game, but Francis Isherwood was a late withdrawal and Burns found himself playing for the auld enemy.

Over the decades the fixture has obviously been a sporting spectacle featuring a disproportionate number of some of the greatest tries ever scored – Richard Sharp, Andy Hancock, Clive Woodward immediately come to mind – along with the pass of the century from Finn Russell and that famous last minute conversion to win the game by No.8 Peter Brown, but it has also been an important staging post.

In 1873, straight after the third ever match between the nations, the great and good met to form the Scottish Rugby Union and then six years later we have the first rugby trophy, the Calcutta Cup, donated by the Calcutta Club after they wound up and had their remaining silver rupees melted and fashioned into a trophy.

1884 saw another bitter dispute when England “played advantage” after a Scottish knock-on and scored a try. This time it was the Scots who were fuming and refused to play England for two years. The argument was only settled when the International Rugby Board (IRB) was set up to mediate and establish a universal law. This is also the fixture which was the first ever televised rugby game in 1938. It is, as they say, a sporting occasion that has plenty of history and baggage.