A weekly look at the game's other talking points

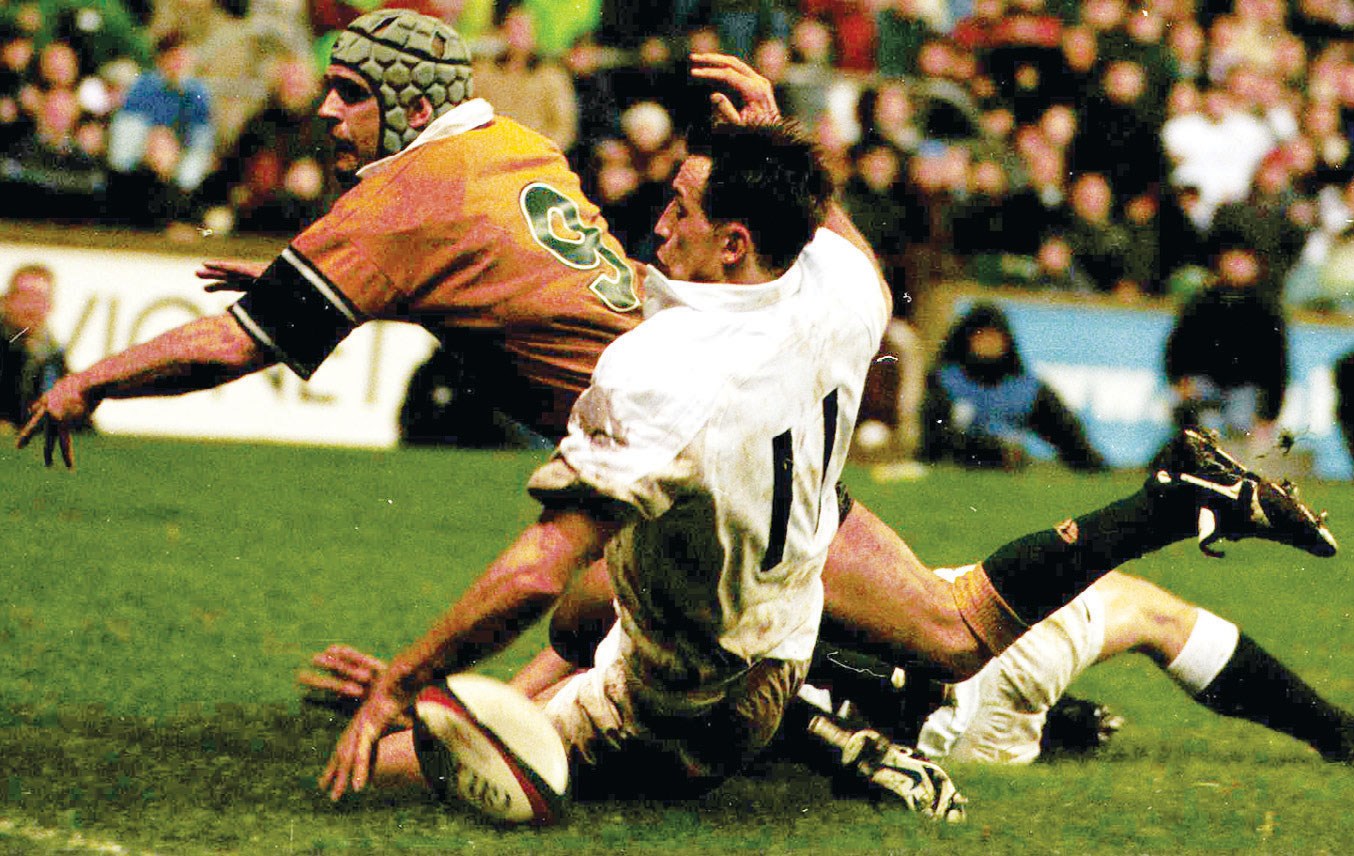

It's 20 years to the day, would you believe, that the Video Ref as it was called back then was used in an international rugby match for the first time. England fans will remember it well with Dan Lugar clinching a lastminute England win over Australia at Twickenham on November 15, 2000 – a victory that put Clive Woodward's England well and truly on the way to eventual glory.

Despite the passage of 20 years the TMO – as it has now become – still feels like a work in progress, an evolving project and a matter of on-going debate. It has the ability to offer up definitive clarity on many occasions – perhaps even the majority of occasions – but often it still leaves questions unanswered and we return to the original concept that the referee's word is final, even when he or she is wrong. Which then begs the old question: why use it all? Or at least why isn't it simply confined to the try-scoring decisions which was its sole raison d'etre back in 2000, and for a few years after that as well.

By any criteria the TMO has become increasingly obtrusive, long-winded and irritating. It can stretch games to well over two hours and often takes the steam and passion out of a contest just when it was beginning to hot up. There can unquestionably be a good deal of drama and theatre surrounding a crucial try-scoring decision. But you can hear the balloon deflating as officialdom spends an eternity examining some real or imagined incident of foul play; or an alleged offside as a player charges down a kick, or chases a kick through; or the impatience as the TV director struggles to get the right angle and camera shot to adjudicate on a forward pass or somesuch.

Was that ball really knocked on or did it in fact go backwards? Has that boot grazed the touchline or is the heel actually above the touchline and not in contact with it? Did the scrum-half fractionally lift that ball at the base of the ruck, and was therefore fair game, or not? Did defender x take the ball over the try line before he touched down or had the ball already crossed? Scrum five or drop out 22? And so on.

The Video Ref/TMO was never ever intended for such minutiae. If you want to go down that route some rugby matches would never finish. But once the genie was out of the bottle that was always the danger with the game increasingly a slave to technology rather than its master. The irony of course is that while some decisions are measured in millimetres, lineouts are often called 10-15 metres from where a ball actually went into touch and scrum-halves still put the ball into their second row at scrum time.

The rot set in right at the start, in that first instance of its use at Twickenham, and the clue is in that early phrase Video Ref. The decisionmaking process was taken out of the referee's hands, he ceded authority, and frankly has been struggling to regain it ever since.

On that murky November afternoon referee Andre Watson wasn't sure whether Dan Luger had managed to get a hand to Iain Balshaw's chip ahead so, rather nervously, he referred it to that new-fangled invention, the eye in the sky, on this occasion international referee Brian Stirling.

At which point the referee's involvement ended. No joint consultation of the big screen – there was no big screen – no methodically going through the law relating to what constitutes a touchdown. What communications there were seems akin to the Apollo moonshot, muffled distant voices operating on a four or five second time delay.

As the cameraman homed in on Watson you could clearly hear the South African shouting above the noise, seemingly for the benefit of the TV viewer: “I'm waiting for Brian to tell me.” Eventually the word comes down from on high. Brian had spoken. Try. Mind you looking at it again – literally with 2020 vision – I have my doubts. It was a complete swing of a call to have to make first time up. While grabbing the ball at the top of its bounce with his left hand Luger appears to then lose control on the way down and the only contact between the ball and MotherEarth is with the upper part of his back as he continues to slide through feet first. Does that constitute a try?

Neil Back in support declined to dob the ball down to make doubly sure – shades of Roger Hunt not popping the ball over the West German line at Wembley in 1966 after Geoff Hurst's disputed second goal.

Ever since then the use of the TMO has featured this unspoken power struggle between the referee, out of breath and sweating out on the paddock, and the TMO luxuriating with a coffee in front of his bank of TV monitors. Improved communications have helped – barring technical difficulties – the referee now gets to see the same pictures as the TMO on the big screen but the arm wrestle continues. Often the referee is only looking at those pictures at the insistence of the TMO, so from the off the referee is immediately on the back foot.

His call is implicitly being questioned. Increasingly the TMO leads the referee through pictures that he, the TMO, has already selected and viewed a couple of times. Often you can hear their preference and recommendation in their voices.

Indeed some – distinguished Test referees or former Test referees in their own right – simply state what the decision must be which is well beyond their remit.

So, on the eve of a new domestic season, and for the benefit of those who sometimes struggle to keep up with the latest procedure, here is the headline passage from the current, lengthy, World Rugby guidelines on TMO protocol: “The TMO is a tool to help referees and assistant referees. The referee should not be subservient to the system. The referee is responsible for managing the TMO process. The referee is the decision maker and must remain in charge of the game.” Amen to that.