Brendan Gallagher concludes his expert and authoritative look at the history of Rugby Union

The History of Rugby: PART 20 STORY SO FAR… AND WHAT THE FUTURE HOLDS

EMBARKING on a quickfire ‘history of rugby' has been an interesting project and we conclude this week with an overview – if such a thing is possible – of “the story so far” and a few speculative suggestions as to how it will develop in the future. Only a madman would seriously attempt the latter given the current state of flux but, hey ho. Why not?

What hits you straight between the eyes is that the game's development has been random and unplanned, full of schisms, fights, politics, self-interest, closed shops and falling outs among thieves. It makes for a vivid, interesting but frustrating story, full of missed opportunities as well of moments of high achievement.

There are probably five key dates to bear in mind: 1871, which formalised rugby's split with football, saw the formation of the RFU and the redrafting of the laws; 1895 which effectively banned professionalism within the game and saw Rugby League go its own way; 1987 and the first World Cup; 1995 when Rugby Union became Open and finally, I would suggest, 2020!

Rugby has been forced onto another cliff edge in recent months although in fairness it was heading there well before Covid-19.

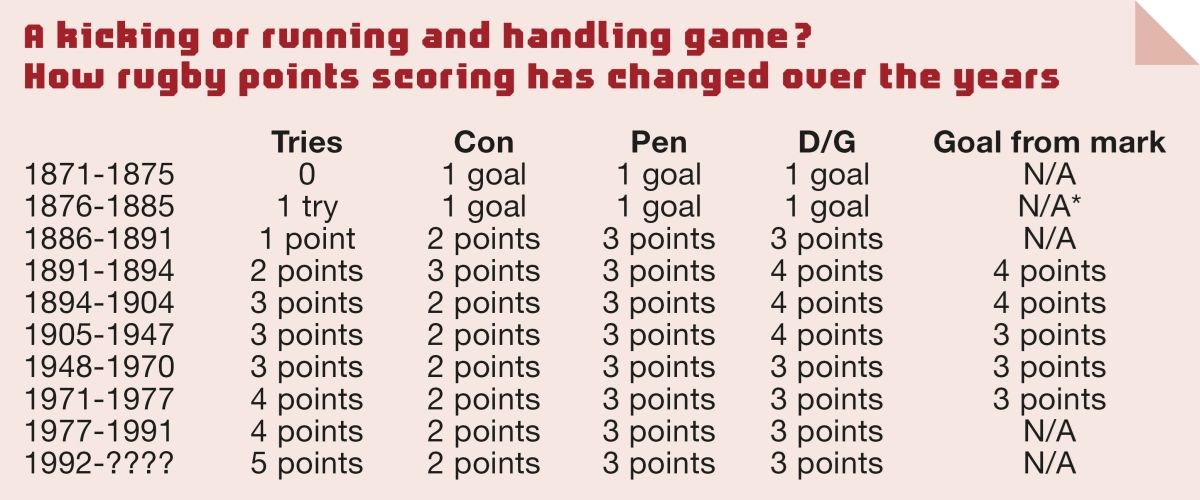

Going forward the club and Test scene must be radically altered if it is to be fit for purpose for the rest of the 21st century. Such change can seem a bit scary but actually it will just be another chapter in the game's development. It's perfectly normal. Given the long lens of history we can see that for a long time rugby endured a massive identity crisis. Was it a kicking or handling game? It wasn't football but what exactly was it? Closely related to football, it started off as a kicking game with tries having absolutely no scoring value other than earning the attacking team a kick at goal. It was goals scored that decided the winner. However over a period of 122 years (1871-1993) the try morphed from being valueless to now being worth five points.

Rugby also started off, like cricket, as a game of Empire and with one or two exceptions, it struggled for many decades to shake of those shackles.

That's where rugby is very random though. Why did France adopt rugby but not cricket with ideal conditions existing in France for both games? And why, after the French took to rugby so heartily, were other non- Empire countries not embraced and brought into the fold more readily?

Rugby had little missionary zeal. By 1890 the IRB consisted of the four Home Unions but even Australia, New Zealand and South Africa – the last two being the strongest teams in the world for much of the time – weren't allowed to become full members until 1949. France was barred until 1978. Only in 1987 were representatives of other nations even allowed to attend IRB meetings as delegates.

Contrast this with basketball which sold itself to the world almost from the moment it was invented in the 1890s and is now unquestionably the second most important and popular team sport. It had a European Nations Championship up and running by 1936 and a bi-annual World Championship with subsidiary qualifying tournament in place by 1950. As with football the laws of basketball are very simple. Anybody can learn to play basketball very quickly.

Which begs the question why did rugby allow its laws to become so fiendishly complicated and yet so open to interpretation? My gut feeling is that it was mainly an intellectual, egodriven, arrogance. The more laws that exist the greater the temptation, and the greater the reward, for those clever enough to break them or better still finding unsuspected ways round them.

With some clear exceptions – South Wales, Gloucestershire, Cornwall, Limerick – rugby was a middle class and upper middle class sport of the educated elite in the early formative years and that intellectual challenge of ‘beating' or ‘hoodwinking' the ref, massaging laws and beating the system became ing rained.

Also as football quickly took the world over, rugby in a strange way consciously set itself up as the antithesis of football. Rugby's complexity, its endless laws, and its ability to embrace all shapes and sizes started defining the sport.

All this can sound a little negative, yet as rugby went its own idiosyncratic way it also built up an enviable reputation of good fellowship, respect for the referee and often – but not always – admirable sporting ethics on the field of play. That comradeship, unselfish teamwork and – until recently – the downplaying of individual stardom has always been much admired throughout the sporting, and indeed corporate, world with captains of industry often seeing a transferable template for their own world.

Generally rugby is a good brand to be associated with and that remains the case despite what we assume will be an inevitable Covid downturn in the short term. Although not free from performing enhancing drugs (PEDSs), rugby generally has the situation under control and is not blighted by doping controversies like athletics, swimming and cycling.

A “rugby family” exists even if that expression seems a little corny. The game has always provided an invisible passport into other areas of life, a masonic handshake if you like, which can help with job prospects or simply ensure that a lifelong friendship can be struck up over a few pints in a noisy clubhouse or bar.

There is also a brotherhood among elite players that other sports envy and which persists in the professional game. There is a large element of unspoken fear in rugby, you are going to feel physical pain at some stage, you are going to get hurt and possibly injured. As players you face that together even if on any given day you are opponents on the field and I have long been convinced that the traditional post-match beers with the opposition starts off as an expression of mutual relief/celebration at getting through to the end of the day unscathed. Whatever the result you are both winners.

Such camaraderie among opponents meant that, for example, it was in no way surprising that England ignored IRA threats to play Ireland in Dublin in 1973 while it is also at the heart of why rugby players made such reliable and brave combatants in two world wars.

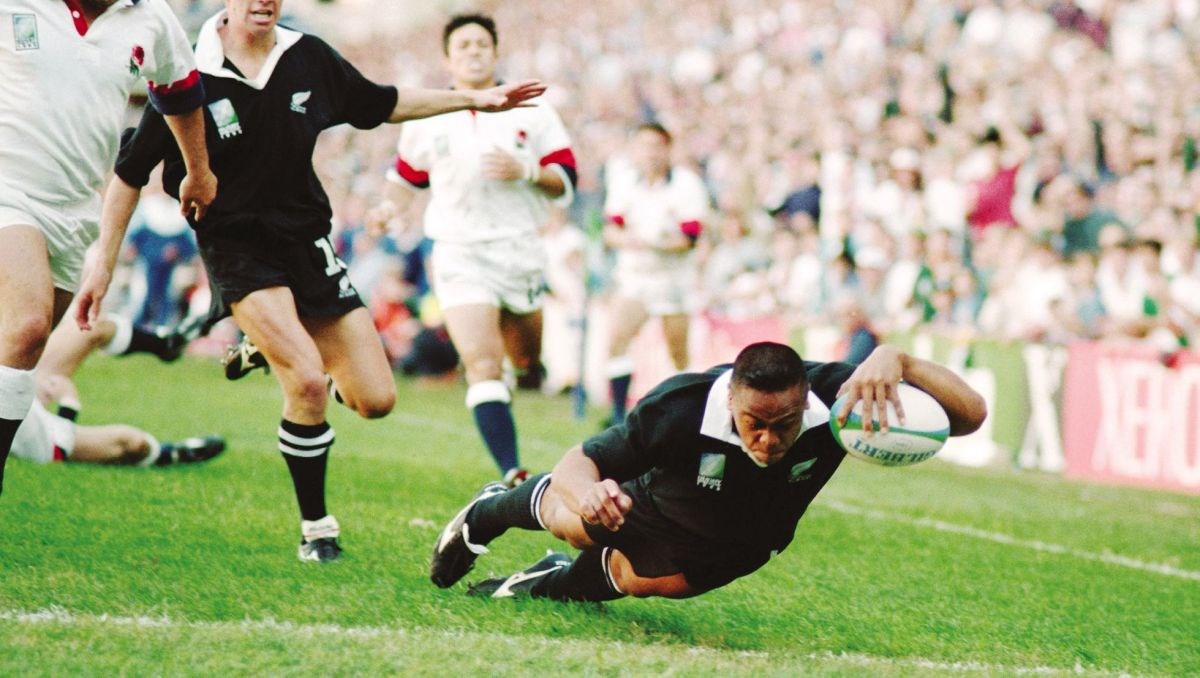

At its very best rugby has shown itself to be the best team sport on the planet – I will brook no argument on this. Played by elite players who understand the laws in front of passionate fans in a game controlled by referees who cannot be fooled yet at the same time allow common sense to be part of the equation. That is sporting heaven. Jonah at Newlands against England in 1995; the 2009 Lions series; New Zealand in full flow against the 2005 Lions and at RWC2015; England beating the Kiwis at RWC2019. The tension of the 2003 World Cup final; the drama of Ireland's Grand Slam in 2009; Wales running riot in Cardiff, the French in full cry in Paris. Nothing touches it.

Rugby has also become synonymous with great stadia and citadels. Lansdowne Road, which was the oldest Test ground of all, Murrayfield, Cardiff Arms Park, Twickenham, Newlands, Loftus Versveld, Eden Park, Stade Colombes, Parc des Princes. Yet a fragile dynamic has always existed, a false illusion of financial solidity. Rugby's big showpiece events sell out, they become occasions of patriotic fervour that transcend the sport but that mass support is rarely widespread as with football. In rugby it often seems feast or famine and it has always struggled with that.

It's quite clear reviewing rugby's timeline that the sport, historically, was horribly complacent and missed all kinds of opportunities. Our rugby forefathers were too pleased with themselves for far too long. Too busy having a good time. The RFU, the governing body of the wealthiest rugby nation on the planet, took 92 years before it organised an overseas tour, finally heading down to New Zealand in 1963. For decades all the Home Unions – frightened and suspicious of change – violently fought off any suggestion of a World Cup or extending the Five Nations Championship. Many ambitious nations were simply blackballed from their cosy club.

A brilliant innovative performance such as the Fijians thrashing a Lionsstrength Barbarians 1970 was treated as an entertaining curiosity rather than the massive shot in the arm it could have been for the global sport. Argentina beat a strong Wales squad in 1968 and probably deserved to beat arguably the strongest Wales side in history at the Arms Park in 1976 but there was simply no thought of getting the Pumas more involved. Not wanted.

When Romania attracted a 95,000 crowd in Bucharest for their game against France in 1957 it was shrugged off as one of those inexplicable things that happen in Eastern Europe. Fancy that, who would have thought! Further afield Tonga beat Australia, four tries to one, in Brisbane in 1973 but weren't offered another Test against an IRB founder member nation for 13 years. In the early 90s the newly constituted Namibia team distinguished itself in quick succession in home Tests against Ireland Italy and Wales but then the Test games against top opposition dried up overnight and Namibia went into a steep decline. Not wanted. At the same time rugby can be unpleasantly predatory and acquisitive.

Rather than spread the gospel and set up a world game, it has often been much easier to simply annex players from ‘lesser' countries.

Like most close-knit families there have been a few dark secrets and skeletons in the cupboard. The demonisation of Rugby League and those who “went north” was not a noble chapter in the sports history nor was the indignities of shamateurism with top players who regularly filled 70,000 stadium scrabbling around for a few illicit payments to pay the bills while administrators and their wives flew around the world in first class opulence.

And then there was apartheid; because South Africa were such prominent and influential members of the rugby family, the game's movers and shakers went AWOL for far too long when the full horrors of apartheid became commonly known, from say the late 50s onwards. Rugby closed ranks, backed its errant son for nearly three decades and ended up badly tainted with much ground to make up.

Rugby did, however, get lucky when President Mandela saved it's bacon with his clever reverse psychology of making the Springboks the new flag bearers for the Rainbow Nation. There was great kudos in being so strongly associated with Mandela and to its credit, rugby has seized that moment of redemption and kicked on impressively.

It has now become a fully inclusive sport. It has also taken the lead in embracing LBGT communities and has massively upped its game in supporting women's rugby. Despite all its faults which get aired regularly and aren't going to disappear anytime soon there is much to admire about rugby in 2020, even if the journey has been eventful and included some obvious wrong turns and cul de sacs en route.

TEN CHANGES AND DEVELOPMENTS TO LOOK OUT FOR IN THE COMING DECADES

1: Reduction in number of players

Teams will be reduced from 15 to 14 and then to 13: The pitch is becoming too small for the 30 high-powered athletes. Mankind is much bigger and faster than 100 years ago and rugby players are no different. We can't change the stadia dimensions so at some stage Rugby Union will drop down to 14 and possibly even 13 players.

2: TMO technology will increase not decrease

The genie is out of the bottle: When the public is bombarded with pictures from every angle and there can be little doubt as to what actually happened, there is an unstoppable momentum to act on those images. If you use such technology for one such decision, eventually logic and fairness insists it must be used on all decisions.

3: Matches will become even longer despite Eddie Jones' protestations

Matches of two hours 15 mins, maybe longer, will be the norm as the need to improve the ‘spectator experience' increases and afford more value for money. Rugby will eventually embrace this. The game will be divided into four quarters or perhaps three thirds with ten-minute breaks for fans to refuel with food and drink and review some of the action on the big screen.

4: Rugby will not become a summer game in the northern hemisphere

And that poses a big problem for those wanting a global season. There is just too much to compete with in a northern summer – cricket, Wimbledon, racing, athletics, Tour de France, F1. Football has the European Nations Cups in the summer, World Cups and of course the Olympics. By trial and error northern hemisphere rugby has already colonised the best window it can ever hope for.

5: Tackling

Tackling will revert to the old textbook, no higher than the waist, style of yesteryear. The irony! Reverting to such textbook tackling could be a fraught process though with head injuries and concussion to the tackled player being replaced by head injuries and concussion to the tackler. Clouting ball carriers around the head, neck or even upper torso is, however, no longer a “look” rugby is prepared to tolerate.

6: The scrum will be depowered

This will change the nature of the game fundamentally, not necessarily for the better but the bottom line is that the majority of the viewing, paying, public are no longer willing to tolerate endless resets and faffing around. They are paying a lot of money to watch and the meter is running. The consumer now rules, rugby ceased to be a game for the players a long time ago. In a matter of years it will be just the one reset before a team is penalised. There might, hopefully, be a special dispensation for scrum fives.

7: Fewer replacements

Five replacements – with three front row compulsory -will become the new norm sooner rather than later. Nothing has disfigured the game more in recent years – and made it more dangerous – than fit, fresh, players coming on for a quick-fire 20 minutes shift against tiring opponents. Nothing is more intrinsically unfair than one player getting the better of his opponent for 50 minutes only to find that ‘bettered' and defeated opponent being replaced.

8: The clear out will be outlawed

The clear out will be re-assessed as the ridiculous license to maim that it has become with securing or clearing the ball almost an irrelevance. They have always been illegal but tolerated much too long. The change to tackling will help this process, there will be more off-loads and less ‘breakdown' situations.

9: There will be two World Cups

The first will consist of the top 12 teams in the world augmented by the semi-finalists of a second “Challenger” World Cup – consisting of 16 teams -which will be held the previous year. There will also be a qualifying competition in the year preceding the Challenger World Cup.

10: World-beating South African and South Pacific domestic competitions

The Springboks have won three of the seven World Cups they have competed and breed more quality rugby players than any nation. If they keep them at home for a part of every season in a pumped up Currie Cup-style competition and augment that with two franchises from Argentina and one from Uruguay you will have a tournament that the rest of the world would want to watch that would attract big TV money. Similarly a domestic South Pacific tournament will be become a reality – three Aussie teams, five Kiwi and two Pacific Island franchises. Financially rugby may need to court the next Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos to help finance this, arguing the case for economic regeneration in the South Pacific.