THE MAN TRULY IN THE KNOW

ONE Sunday afternoon in Watford 20 years ago, Saracens hosted a match designed to herald the advent of rugby as a truly pan-European sport. Dinamo Bucharest turned up at Vicarage Road further handicapped by the discovery that one of their back row forwards, Florin Pradais, had done a runner. He did so for reasons that had nothing to do with the previous week's result in Romania, nor with the reality that to the lop-sided state of the tie was about to get a whole lot more so.

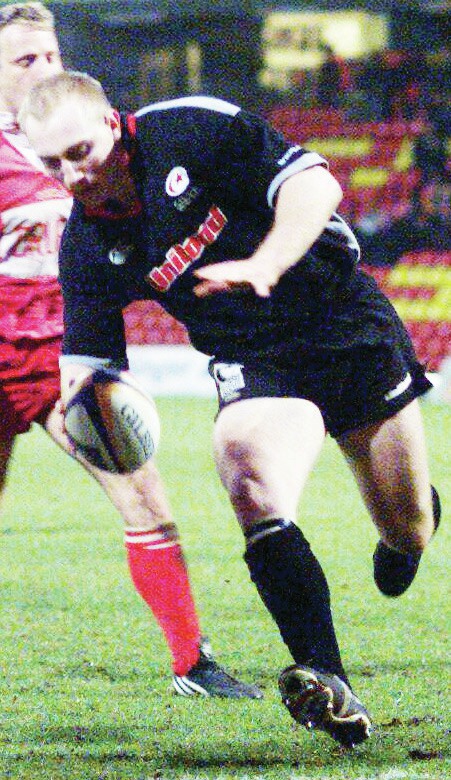

What happened made the result of the away leg, Dinamo 11 Sarries 87, seem a close-run thing. “The changing rooms were about a five-minute walk to the pitch,'' says Tom Shanklin, the Welshman who delivered five tries from the left wing. “So all you could hear along the winding road was the sound of studs on concrete.

“They were so far off what was required that it was like a training game. You could go out and play with a smile on your face because you knew it was going to be easy and you might score a try.''

Sarries scored 23 in the return distributed among 14 players, including only one more for Shanklin. The endless barrage had Dinamo lining up behind their posts every threeand-a-bit minutes for a conglomerate of conversions, 18 of which cost them another 36 points towards the final total: 151-0.

Every other attempt by the organisers, Europe Rugby Ltd, to justify their title with a little continental inclusivity served only to emphasise the gulf between the Six Nations and the rest.

Cetransa El Salvador's two seasons in the Challenge Cup added up to 12 straight defeats for the Villadolid club at an average of 60-plus points. The Spanish national team had tried before that and their two seasons of 12 losses out of 12 worked out an average of almost 45 points. Other Spanish clubs took the plunge only to suffer the same fate, among them La Moraleja Alcobendas from a suburb of Madrid of such affluence that former residents included David Beckham and that well-known team player, Cristiano Ronaldo.

Portugal's one season inflicted an average beating of 62-12 on their national squad. When one of their clubs, Associacao Coimbra, gamely put their heads above the parapet, Bordeaux filled their boots to the tune of 205-10 over two mis-matches.

In the five years before Dinamo's dynamo went to pieces, the game's power-brokers set lofty ambitions to widen rugby's narrow version of Europe beyond the boundaries of Galway in the west and Rome in the east. The then RFU chairman, the late Cliff Brittle, a divisive figure at the epicentre of Twickenham's demoralising war against club owners like Sir John Hall and Nigel Wray, would tell anyone who cared to listen: “What we need is a strong Germany.''

He meant it, of course, in a strictly rugby sense as if somewhere in Bavaria scientists were engineering a Bayern Munich XV capable of taking the English clubs and Irish provinces by storm.

Nobody could accuse Europe Rugby Ltd of not trying. They initiated a third-tier competition for clubs from the continent's second tier nations: Georgia, Portugal, Russia, Belguim, Germany and Spain.

After two seasons won by Enisei-STM from Siberia, they gave it up as a bad job. And now, far from reaching new frontiers, Europe Rugby Ltd presides over a continent which, in rugby terms, has contracted to the bare bones. The Champions Cup has shrunk to Six Nations minus one, Italy, rather than undermine the grandiosity of its title by allowing the solitary Italian qualifier to do so from the nether regions of what used to be the PRO12.

In strictly European terms they have fewer countries now than when the Heineken Cup began in 1995. Then, despite the boycott of the English clubs as part of their political wrangle with the RFU, they had six: France, Ireland, Italy, Romania, Scotland and Wales.

From an original field of 12, Welsh clubs accounted for a quarter through Cardiff, Pontypridd and Swansea. The impoverished state of their four regions is such that Wales now have one out of 20 in the Champions Cup and are lucky to have that many in the face of rising competition.

Continental Europe having turned a collectively deaf ear to the most zealous evangelist, the organisers have ploughed ahead in a different direction, finding new frontiers in another continent where they knew they would be preaching to the converted. While South Africa's three contenders for the Champions Cup will make winning it all the more demanding, problems are already emerging which point to a less than perfect marriage.

Issues over long, convoluted travel as well as exposing British and Irish teams to going from the deep freeze of mid-winter to the heat of the South African summer do nothing for player-welfare, just as the absence of travelling fans does nothing for the box-office.

It has to do for now but only until everyone in the four home countries agrees to a concept which ought to have been blindingly obvious for some time – aBritish and Irish League. Twenty teams – ten English, four Irish, four Welsh, two Scottish – split into two divisions with the top two, or top four, in each qualifying for the knock-out stage. Besides serious competition, it offers what the Champions Cup does not, like the resurrection of traditional Anglo-Welsh fixtures, a new dimension to Ireland's historic inter-provincial championship and affordable travel for fans.

Meanwhile, Europe Rugby Ltd sounds still more of a misnomer than it was last season…