The inspirational deeds of many Rugby players on the Western Front have been well documented in recent years in a number of books and will be commemorated you suspect for much of the next four years. Rugby players clearly tended to make exemplary officers.

The inspirational deeds of many Rugby players on the Western Front have been well documented in recent years in a number of books and will be commemorated you suspect for much of the next four years. Rugby players clearly tended to make exemplary officers.

What is perhaps less well known is a series of high-profile games played by a New Zealand Army XV of near All Blacks Test strength in what was left of North-east France and Belgium in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of the Somme early in 1917.

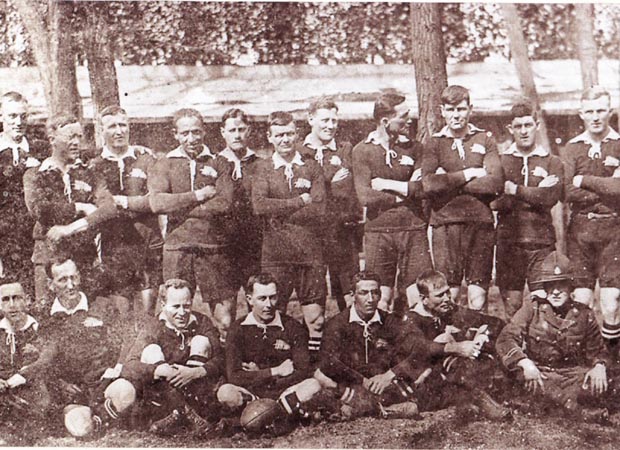

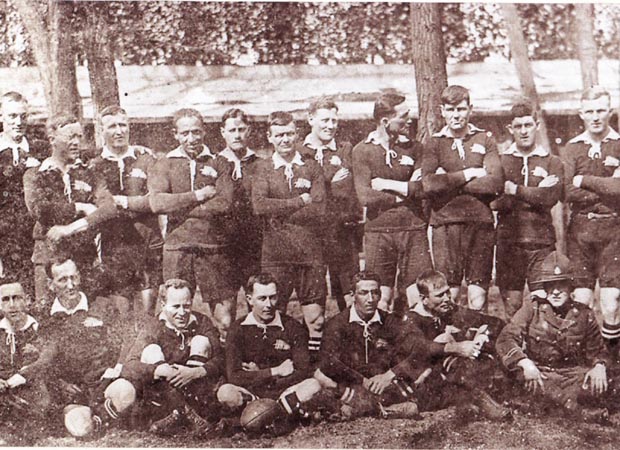

Retrospectively dubbed the ‘Trench Blacks' because, to a man, they were Western Front veterans, they played to keep fit, let of steam and stay sane before they were redirected to the action. Their internal tour of 1917 culminated in the Coupe de Somme – it could just as easily been named the Survivors Cup – against what was advertised as a full France XV many of whose players were called from their trench positions just a couple of days before the match in Paris on 7 April, 1917.

The first Battle of the Somme had started on July 1 and “ended” on November 18 with over a million casualties in total. Over 350,000 British soldiers were either killed or seriously injured and of the 20,000 strong New Zealand Division at the time an estimated 7,400 were either killed or injured during the carnage.

As the 1916-17 winter set in two exhausted armies, subconsciously or otherwise, wearily settled for the status quo. Comparative peace descended on the Western Front for five months or so – a blessed ‘time out' – although there were a couple of minor skirmishes.

In such extreme circumstance what soldiers crave most is normality and those in charge seized the opportunity to withdraw as many frontline troops as possible for a period of rest, recuperation and retraining behind the lines. Field Marshall Haig had also concluded that superior physical fitness was going to be one of the keys going forward and put a Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Plugge in charge of co-ordinating a sports and fitness programme for all Allied troops that winter: boxing, football, rugby, running and general physical training.

Mindful of those orders the New Zealand Division took the opportunity to round up their best rugby players scattered around the Western Front, train them up at one of their ‘divisional schools' behind the lines before embarking on their internal tour challenging any Division or gathering of fellow survivors who could give them a game.

If ever there is a Rugby play with a difference to be written this is it.

Over 40 All Blacks of recent vintage were serving in France – and 13 were to make the ultimate sacrifice – so the squad was of near Test strength with seven All Blacks. And they were extremely fit. For three months after Christmas 1916 they had virtually led the life of professional sportsmen with a rigorous routine and, for once, ample food and sleep: 7am PT; 9am-1pm bayonet and bombing practice; 2.30-4-30pm rugby training, practice matches and games. Seven days a week. And on three nights a week there would be work outs in a local school gymnasium.

Not surprisingly, with such talent to hand and such a level of fitness, the Trench Blacks made short work of most of the opposition who were similarly trying to regroup during a lull in military proceedings. In the nine matches they scored 376 points to nine. Only a very strong Welsh Division full of Wales internationals were able to seriously trouble them. Malcolm Ross, war correspondent of the Dominion newspaper in Wellington, paints a surreal scene of their 18-3 win over the Welsh in a muddy field outside an unidentified Trappist monastery in Belgium close to the front-line. Indeed there is more than a hint of Monty Python and Blackadder about it:

“Generals and many officers were present and a regimental band played before the commencement and during the half-time interval. Some of the local people who had never seen a rugby football match were also there and on the outskirts of the crowd, also interested, but not greatly understanding were big tonsured monks in their flowing robes from the adjoining monastery.

“Close at hand a great captive balloon swung in the air and at intervals came the report of a bursting shell flung from the Boche lines. A Belgian prince was among the spectators and to him and one of the monks I had to explain the intricacies of the game.”

As the Belgian Trappist monasteries produce – then and now – probably the best beer in the world one can safely assume that even in the middle of the “War to end all Wars” the hospitality would have been good that evening.

The high-profile ‘Test' against France was a remarkable occasion in many ways and played in a carnival atmosphere after the USA had officially entered the War the day before, prompting unrealistic and short-lived hopes of a German climbdown or even a surrender.

The game was organised mainly by the French newspaper Le Journal and played at the famous Vincennes Velodrome which was the main stadia for the 1900 Paris Olympics although the athletics were held elsewhere. For a short while late in its history 1968-74 – it also hosted the final day of the Tour de France and therefore played host to all of Eddy Merckx's five Tour wins.

In his report Ross claims a world record crowd of 60,000 attended the game but also admits elsewhere in his dispatch that he was unable to attend personally and pictures from game suggest other reports of a crowd in the region of 25,000 might be closer to the mark. Whatever the case, the stadium was undoubtedly rammed.

“The reception of the team at the match and generally in the few days they were in Paris was extraordinarily enthusiastic,” confirmed Ross in his report. “They were there at a memorable time. The news of the declaration of War against Germany by the USA has just come to hand and in honour of the event the tricolour was fluttering in every street in Paris and in the streets of every town and village behind the battle zone in France.”

The New Zealand XV were at a huge advantage, having trained and played together for two months throughout the winter. The French team, with eight capped players, meanwhile, were thrown together at the last possible moment with an emergency letter going out to 23 French generals the week before requesting the immediate release of the players if they could be spared. A number came straight from combat action, the smell and grime of battle still on their tunics as they arrived at the Vincennes changing rooms.

Burly forward Capitan Alfred Eluere had been involved in a firefight with his tank engagement at 5.30pm the previous evening. Skipper Maurice Boyau, the renowned fighter ace and balloon buster who served as a pilot in Escadrille 77 – Les Sportifs as they were known – had endured a busy fortnight with the Service Aeronautique before the game.

That spell of active service had included Boyau's first ‘kill' – or victory as they are now known – when he avenged the death of his colleague Lieutenant Havet who has been shot down while they were on patrol together. Boyau gave chase to the German Aviatik and duly gunned him down. Boyau was to amass 14 victories and 21 balloons in his career which earned him the Medaille Militaire and the Legion d'Honneur before he was shot down and killed by German ace Georg von Hantelmann on 16 August, 1918.

Boyau's medal action was a particularly dramatic affair having made a forced landing behind German lines after claiming a heavily defended balloon. With German infantry racing to the scene to take Boyau prisoner he effected a rapid repair and took off again in a hail of enemy fire as the troops arrived just seconds too late.

Another not to survive the War was forward Conilh de Beyessac, a descendant of one of Napoleon's most trusted generals, who had been a member of Rosslyn Park circa 1910-11 although there is no record of him making a first team appearance. De Beyessac, a Tank Division officer, died of his wounds in June 1918, aged 28, and is buried at St Remy l'Eau, Oise.

In the New Zealand line-up was flanker Reg Taylor, capped against Australia just before the War. Having been sent to Europe Taylor survived the horrors of Gallipoli and the Somme, an indeed the first two weeks of the Battle of Messines two months after the game in Paris before his luck ran out. He was killed serving with the 1st Battalion of the Wellington Regiment on June 20.

Perhaps the best known Kiwi was Arthur “Ranji” Wilson, generally reckoned to be the best flanker on the planet leading into WW1. Wilson was a star turn for the Trench Blacks and was the centre of controversy soon after the War when the New Zealand team returned via South Africa and a 15-match tour.

Because of his mixed race parentage – English and West Indian – Wilson was classified as a “coloured” and not allowed to tour and Parekura Tureia of the 28th Maori Pioneers Regiment was another also barred on racial grounds. Tureia also served in WW2, rising to captain, but was killed in North Africa in November 1941,

Observers insist the game was closer than the score suggests but that was probably down to war-time diplomacy among allies. New Zealand, after performing the haka which apparently caused much hilarity among the crowd, took France apart. Le Journal proclaimed that “the exhibition of rugby was one of the best ever seen in Paris, and the Blacks, as usual, kept the game fast and open.”

After the game came the really serious business, the third half. Ross takes up the story: “The journey from the gates back to Paris was in the nature of a triumphal procession. The crowds again gave vent to their enthusiasm and women rushed forward to kiss the New Zealand heroes.

“In Paris the members of the team were feted right royally. They were banqueted by Le Journal and invited to clubs, had seats reserved at theatres. Le Journal presented them with a spirited statue in bronze by the sculptor Chauvel designed while he himself was in the trenches. It is perhaps the most unique memento of our participation in the War.

“In addition each of the ‘athletes and heroes' received a beautiful medallion in frosted silver on which is the famous figure in relief of La Marseillaise from the Arc de Triomphe. They were also given tinder boxes of solid gold or gold and silver. They had the time of their lives.”

Indeed but the party was over. In a matter of days it was back to the killing fields of Flanders although a smaller party made a flying trip to the New Zealand Hospital at Amiens to play a game. Quite who provided the opposition at a hospital is unclear but regardless it was time for the ‘battle season' to recommence.

In a matter of days all the rugby tourists were back on duty, packing down in the squalid trenches again, scrambling around trying to keep their gold tinder boxes dry, the many charms of Paris long forgotten. Suggestions of an early ceasefire sparked by the balance of power tipping hugely in favour of the Allies now bolstered by the USA had quickly faded.

It was back to the madness. The huge deadly battles of Messines, Ypres, Passchendaele and Cambrai lay ahead.

Suddenly all thoughts of rugby were put to one side but Paris had been fun while it lasted, a tonic for the troops.